B.

The Nation’s No. 2 State Lobby

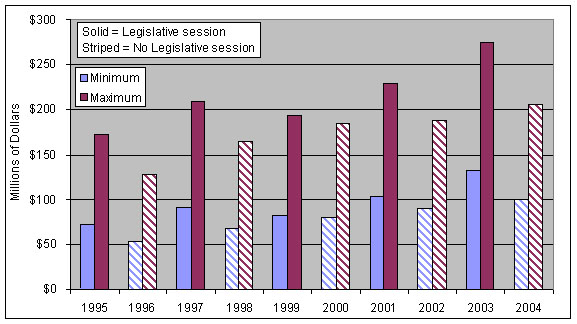

The adage “Everything’s bigger in

Texas” is difficult to prove or disprove where lobby expenditures are concerned.

A kaleidoscope of different state lobby reporting requirements subjects

any state lobby ranking to numerous caveats. Under Pressure, a recent

study by the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Public Integrity, found

that Texas had the nation’s second-highest lobby expenditures in 2003 after

California. Yet the $191 million figure that Under Pressure uses

for California is based on the actual value of lobby contracts.

In contrast, the $137 million figure that the same study uses for the Lone

Star State is based on the minimum value of Texas’ lobby contracts.

Texas braggarts will note that the $276 million maximum value of

Texas lobby contracts far exceeds the $191 million in California lobby

expenditures.

C.

Million-Dollar Clients

The remainder of this report analyzes

the 6,593 paid Texas lobby contracts reported by the end of 2003.

The 1,578 lobbyists who reported these contracts said that they were worth

a total of between $132 million and $276 million (Texas lobbyists report

contract values in ranges: e.g. “$50,000 - $99,999”).

By the end of 2003, 17 mega-clients

had maximum lobby expenditures of more than $1 million apiece (the appendix

lists Texas’ top 100 lobby clients). These 17 mega-clients collectively

spent up to $30.4 million, accounting for 11 percent of Texas’ total reported

lobby expenditures. As usual, SBC (Southwestern Bell) was far and away

Texas’ top lobby client, spending up to $7.6 million on 110 staff and freelance

lobbyists in 2003.

Million-Dollar Clients

| 2003 Lobby Client |

Contract

Value (Max.) |

Contract

Value (Min.) |

No. of

Contracts |

| SBC (Southwestern Bell) |

$7,570,000 |

$3,935,000 |

110 |

| TX Utilities Co. (TXU) |

$1,920,000 |

$870,000 |

55 |

| EDS (Electronic Data Systems) |

$1,860,000 |

$1,300,000 |

16 |

| TX Medical Association |

$1,725,000 |

$935,000 |

24 |

| City of Houston |

$1,705,002 |

$1,010,000 |

32 |

| Assn. of Electric Companies of TX |

$1,675,000 |

$785,000 |

30 |

| Verizon |

$1,665,000 |

$735,000 |

45 |

| City of Austin |

$1,510,000 |

$750,000 |

22 |

| AT&T Corp. |

$1,475,000 |

$720,000 |

29 |

| CenterPoint Energy |

$1,395,000 |

$700,000 |

21 |

| ExxonMobil Corp. |

$1,250,000 |

$735,000 |

19 |

| TX Hospital Assn. |

$1,225,000 |

$610,000 |

19 |

| Metro. Transit Authority of Harris County |

$1,165,000 |

$560,000 |

20 |

| McGinnis Lochridge & Kilgore |

$1,075,004 |

$960,000 |

7 |

| TX Assn. of Realtors |

$1,075,001 |

$685,000 |

10 |

| Affiliated Computer Services (ACS) |

$1,060,000 |

$520,000 |

19 |

| TX Assn. of School Boards |

$1,050,000 |

$525,000 |

12 |

D.

Clients By Interest Category

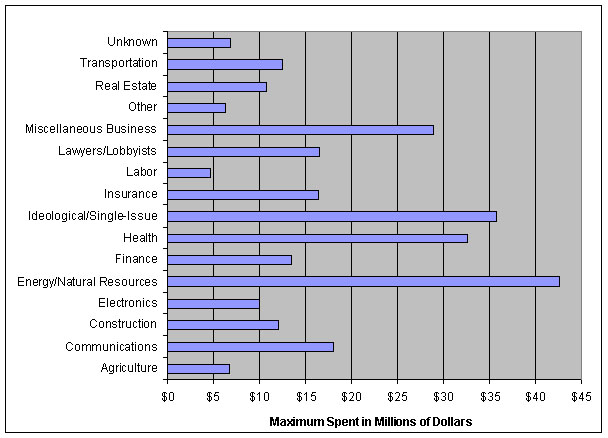

This report categorizes Texas’ 2003

lobby contracts by their underlying interests. Energy & Natural Resources

is the leading category, accounting for 16 percent of all lobby money.

The next largest categories are: Ideological & Single-Issue clients;

Health; and Miscellaneous Business.

Lobby Contracts By Interest

Category

| Interest

Category |

Max. Value

of Contracts |

Min. Value

of Contracts |

No. of

Contracts |

Percent

(of Max. Value) |

| Agriculture |

$6,815,001 |

$3,130,000 |

174 |

2% |

| Communications |

$18,095,500 |

$8,935,500 |

367 |

7% |

| Construction |

$12,180,002 |

$6,130,000 |

249 |

4% |

| Electronics |

$10,055,000 |

$5,015,000 |

217 |

4% |

| Energy & Natural Resources |

$42,800,004 |

$21,230,000 |

908 |

16% |

| Finance |

$13,595,001 |

$6,095,000 |

342 |

5% |

| Health |

$32,720,001 |

$15,245,000 |

822 |

12% |

| Ideological & Single Issue |

$35,850,047 |

$16,980,043 |

917 |

13% |

| Insurance |

$16,485,000 |

$6,795,000 |

548 |

6% |

| Labor |

$4,775,000 |

$2,175,000 |

117 |

2% |

| Lawyers & Lobbyists |

$16,590,018 |

$10,145,000 |

286 |

6% |

| Miscellaneous Business |

$29,045,002 |

$13,900,000 |

694 |

11% |

| Other |

$6,305,000 |

$2,880,000 |

156 |

2% |

| Real Estate |

$10,825,002 |

$5,520,000 |

219 |

4% |

| Transportation |

$12,585,000 |

$5,805,000 |

289 |

5% |

| Unknown |

$6,865,000 |

$2,505,000 |

288 |

2%

|

|

Totals:

|

$275,585,578 |

$132,485,543 |

6,593 |

100% |

|

Energy

& Natural Resources Contracts

The oil, gas and utility interests

that have long ruled Texas dominate the Energy and Natural Resources sector,

which is led by TXU (see “TXU’s Bad Breaks"). With its heavy use of joint

ventures and contractors, this industry stands to benefit from 2003 restrictions

on proportional liability, in which more than one defendant is responsible

for an injury (see “Damages Control”). Energy-industry pollution has created

business opportunities for three other major lobby clients in this sector:

Fuel Cells Texas, Environmental Systems Products Holdings and Waste Control

Specialists.

Fuel Cells Texas represents companies

developing technology that chemically converts fuel to electricity without

burning fuel. Members of this new-age trade group include such old-age

energy and chemical companies as CenterPoint, Hunt Power, ChevronTexaco,

Siemens Westinghouse, Shell and DuPont. These companies know how to jump-start

politicians. Fuel Cells Texas formed in 2001, when the legislature ordered

the State Energy Conservation Office to find ways to promote this technology.

Shortly after President Bush plugged fuel cells in his 2003 State of the

Union address, energy interests announced that they were seeking government

aid to establish an alternative-energy research complex. They then built

their Texas Energy Center at the University of Houston’s new Sugar Land

campus--in the backyard of House Majority Leader Tom DeLay. Governor Perry

announced a $3.6 million grant to the Texas Energy Center in 2004, in one

of the first handouts of his new Texas Enterprise Fund.

The nation’s largest contractor for

vehicle emissions testing, Environmental Systems Products Holdings (ESP)

won a $3.5 million contract in 2001 to supply the Texas Department of Public

Safety with remote-sensing devices, which measure pollution from passing

vehicles. ESP also produces half of the emissions-testing equipment used

around Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth. This testing requirement is expanding

as other Texas cities struggle to comply with federal air-quality laws.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality announced in 2004 that ESP

was fixing a software glitch that improperly flunked some vehicles.

Top Energy & Natural

Resources Clients

| Lobby

Client |

Max Value

Of Contracts |

No. of

Contracts |

| Texas Utilities Co

(TXU) |

$1,920,000 |

55 |

| Assn. of Electric Companies of TX |

$1,675,000 |

30 |

| CenterPoint Energy |

$1,395,000 |

21 |

| ExxonMobil Corp |

$1,250,000 |

19 |

| Fuel Cells TX |

$950,000 |

07 |

| Waste Control Specialists, Inc |

$950,000 |

21 |

| Sentinel Resources Corp. |

$900,000 |

08 |

| Reliant Resources |

$815,000 |

15 |

| Environmental Systems Products Holdings |

$760,000 |

12 |

| Exelon Power TX |

$750,000 |

08 |

| Valero Energy Corp. |

$735,000 |

15 |

| Sempra Energy |

$670,000 |

12 |

| Entergy Corp. |

$655,000 |

20 |

| American Electric Power |

$645,000 |

12 |

| Texas Electric Co-op, Inc |

$625,001 |

08 |

Controlled by Dallas corporate-takeover

billionaire Harold Simmons, Waste Control Specialists (WCS) lobbied for

eight years for permission to dump nuclear waste in West Texas. After the

Simmons family and its Contran holding company gave $435,000 to state politicians

in 2002, the 2003 legislature agreed to let the nation’s nuclear power

plants and federal nuclear weapons sites ship low-level radioactive waste

to the company’s dumps. WCS stands to make billions of dollars off this

law, which saddles taxpayers with long-term liability for this nuclear

waste.

Against citizen opposition, Sentinel

Resources has spent five years seeking a permit for a traditional landfill

south of Houston. Two administrative law judges recommended in June 2004

that the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality reject Sentinel’s application,

which the judges said failed to satisfy water-quality and other concerns.

Ideological

and Single-Issue Contracts

Local governments dominated lobby

contracts in the Ideological and Single-Issue sector. This sector’s top

clients were the state’s largest city and the state capital. Austin clashes

with the legislature more than any other city due to its modest efforts

to protect its local environment.

The public transportation authorities

of Houston, Dallas and Austin also ranked among this sector’s top lobby

clients. All of these entities have hustled dollars and votes for rail

systems in recent years. Austin’s metro authority is revamping its rail

proposal, which voters narrowly derailed in 2000—the same year that Dallas

voters snubbed a bond initiative for their rail system. Houston-area voters

narrowly approved expanding their system in late 2003.

The Texas Civil Justice League and

Texans for Lawsuit Reform lobbied in 2003 for lawsuit limits, led by H.B.

4 (see “Damages Control”). A similar-sounding attorney group, Texans for

Civil Justice, opposed that legislation. The Tigua Indians’ Ysleta Del

Sur Pueblo had a big stake in recent proposals to legalize slot machines

(see “Gambling on Slot Machines”).

The Texas Municipal League (TML) did

not claim much bang for its lobby bucks. TML bemoaned a 2003 ethics law

that requires big-city officials to disclose personal financial information

(as state officials do) and applauded passage of three under-whelming “priorities.”2

Two public entities are involved in

the state’s burgeoning water wars (private water companies are classified

under “Energy and Natural Resources”). The Lower Colorado River Authority

and San Antonio Water System agreed in 2002 to pursue a complex deal in

which the city would fund reservoirs and rural water-conservation projects

along the Colorado River in exchange for a cut of the captured water.

This sector’s leading public-interest

client was the American Cancer Society, which promoted tobacco taxes, the

Children’s Health Insurance Program and an anti-obesity drive for kids.

Top Ideological &

Single-Issue Clients

| Lobby Client |

Max.

Value

Of Contracts |

No.

of

Contracts |

| City of Houston |

$1,705,002 |

32 |

| City of Austin |

$1,510,000 |

22 |

| Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris

County |

$1,165,000 |

20 |

| Texas Civil Justice League |

$990,000 |

23 |

| Texas Municipal League |

$960,000 |

13 |

| Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo Tribal Council |

$900,000 |

7 |

| Lower Colorado River Authority |

$815,000 |

23 |

| Dallas Area Rapid Transit |

$750,000 |

5 |

| Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority |

$750,000 |

5 |

| Texans for Lawsuit Reform |

$675,000 |

13 |

| Port of Houston Authority |

$640,000 |

13 |

| American Cancer Society |

$625,000 |

11 |

| San Antonio Water System |

$610,000 |

8 |

| City of Laredo |

$560,001 |

6 |

| Texans for Civil Justice |

$550,001 |

4 |

Health Contracts

The two trade associations with the

greatest interest in capping damages paid to medical malpractice victims—the

Texas Medical Association and the Texas Hospital Association—led the health

industry lobby. Other doctor and hospital interests that made heavy lobby

expenditures include the Texas Opthalmological Association, the Trinity

Mother Frances Health System3 and Save

Our ER’s, which seeks more Houston-area trauma services. Formed specifically

to cap malpractice damages (see “Doctored Malpractice Claims”), the Texas

Alliance for Patient Access allied medical with health insurance interests.

The top health insurance lobby forces

were PacifiCare, Blue Cross, AMERIGROUP and the Texas Association of Health

Plans trade group. This industry pushed two 2003 bills that now allow insurers

to charge consumers more co-payments and deductibles for fewer covered

benefits.4 The Texas Attorney General also

sued PacifiCare in 2001 for failing to pay medical bills promptly; the

parties partially settled these claims in 2003. Lawmakers passed SB 418

in 2003 in yet another effort to make insurers pay medical bills promptly.

Other major health lobby clients have

stakes in other H.B. 4 lawsuit limits, including nursing home interests

(Mariner) and drug makers. Drug interests (GlaxoSmithKline and the Pharmaceutical

Research & Manufacturers of America) also swarmed a 2003 bill that

established a preferred drug list for Texas Medicaid patients.5

Failing to kill the list outright, drug makers sought exceptions for some

drugs and then lobbied to get their products listed. In 2004 drug makers

GlaxoSmithKline and Bayer agreed to pay $9 million to settle Texas' share

of federal Medicaid fraud charges.

Top Health Clients

| Lobby

Client |

Max. Value

Of Contracts |

No. of

Contracts |

| TX Medical Assn. |

$1,725,000 |

24 |

| TX Hospital Assn. |

$1,225,000 |

19 |

| GlaxoSmithKline |

$800,000 |

7 |

| TX Alliance for Patient Access |

$650,000 |

9 |

| PacifiCare |

$560,000 |

11 |

| TX Ophthalmological Assn. |

$535,000 |

7 |

| McKesson Corp. |

$500,000 |

5 |

| Blue Cross & Blue Shield of TX |

$450,001 |

5 |

| Trinity Mother Frances Health System |

$450,000 |

7 |

| TX Dental Assn. |

$435,000 |

8 |

| Pharmaceutical Research & Manufacturers

of America |

$425,000 |

7 |

| AMERIGROUP Corp. |

$420,000 |

11 |

| TX Assn. of Health Plans |

$405,000 |

8 |

| Mariner Post Acute Network, Inc. |

$400,000 |

7 |

| Save Our ER's |

$400,000 |

8 |

Miscellaneous

Business Contracts

The Miscellaneous Business sector’s

gambling, alcohol and pornography industries have major stakes in the “sin-tax”

debate. Forecasts of massive state budget shortfalls overshadowed Texas’

2003 legislative session. Lawmakers largely addressed the fiscal crunch

in 2003 through spending cuts—postponing the dicey issue of how to increase

revenues for the special session that Governor Perry called in early 2004.

With most lawmakers unwilling to consider a state income tax or closing

corporate tax loopholes, “sin taxes” emerged as the most painless way to

boost revenues. One exception was a failed House proposal to increase the

state sales tax and apply it to previously exempt services (thereby offending

the refined tastes of the Texas Association of Interior Design).

Governor Perry kicked off the 2004

special session with a proposal to raise $7 billion in new revenues, led

by the following sin-taxes:

-

$2.6 billion from cigarettes;6

-

$2 billion from legalizing slot machines;

and

-

$90 million from fees on topless bars.7

The governor’s sin-tax list hit tobacco

but sidestepped the nation’s next two leading causes of preventable deaths:

diet and exercise problems (No. 2); and alcohol (No. 3). This was a coup

for the alcohol lobby, led by Miller Brewing, Wholesale Beer Distributors

and Anheuser-Busch. Similarly, the obesity epidemic is feeding liability

and sin-tax concerns within the junk-food industry (see Kraft and Texas

Soft Drink Association).

Unlike these purveyors of legal sins,

the gambling industry actually lobbied for passage of a new sin tax—if

the state would legalize slot machines at race tracks and Indian reservations

(see “Gambling on Slot Machines”).

Top Miscellaneous Business

Clients

| Lobby Client |

Max.

Value

Of Contracts |

No.

of

Contracts |

| MEC Lone Star |

$750,000 |

5 |

| Miller Brewing Co. |

$705,000 |

13 |

| TX Assn. for Interior Design |

$600,000 |

6 |

| Wholesale Beer Distributors of TX |

$585,000 |

9 |

| Silverleaf Resorts, Inc. |

$560,000 |

8 |

| Rio Grande Valley Partnership |

$500,000 |

5 |

| Amusement & Music Operators of TX |

$480,000 |

10 |

| Kraft Foods North America |

$480,000 |

10 |

| GTECH Corp. |

$450,000 |

4 |

| Oberthur Gaming Technologies |

$410,000 |

6 |

| Crown Cork & Seal |

$400,000 |

8 |

| Anheuser-Busch Co's |

$365,000 |

9 |

| TX Petroleum Marketers & Convenience

Store Assn. |

$355,000 |

9 |

| Greater Fort Bend Economic Development Council |

$325,000 |

4 |

| Gulf Greyhound Partners |

$310,000 |

3 |

| TX Soft Drink Assn. |

$310,000 |

9 |

Dallas-based Silverleaf Resorts has

generated class-action lawsuits and hundreds of complaints with the Better

Business Bureau and the state Attorney General and Real Estate Commission.

Customers have complained that Silverleaf used high-pressure and deceptive

tactics to sell time shares in low-end resorts that reportedly are poorly

maintained. |

Top Lobby States in 2003

| State |

Value

of 2003

Lobby Contracts |

| California |

$191,041,807 |

| Texas |

*$137,402,500 |

| New York |

$120,000,000 |

| Massachusetts |

$58,936,454 |

| Minnesota |

$43,925,842 |

| Washington |

$33,277,396 |

| Maryland |

$30,500,000 |

| Connecticut |

$30,127,231 |

| New Jersey |

$26,672,823 |

| Michigan |

$26,571,893 |

*This

figure exceeds the $132 million minimal value

of 2003

lobby contracts used in this reportbecaus the

Center's

study also includes lobbyists' wining-and-

dining

expenditures. |

Damages

Control: The Lawsuit-

Protection

Lobby

Spores of the biggest business

lobby coup of 2003—a new crop of lawsuit limits—may have germinated in

2001, when Rep. Joe Nixon filed mold claims on his $369,500 home. Farmers

Insurance, which initially paid $300,000 on the lawmaker’s mold claims,

paid Nixon another $13,000 more during the 2003 legislative session for

damage that contractors did to Nixon’s yard. A whistle-blowing Farmer’s

mold manager complained that her superiors “strong armed” this extra payment

to curry favor with a powerful lawmaker, a complaint that Travis County

prosecutors rejected. Nonetheless, “Moldy Joe” Nixon emerged as the insurance

industry’s best friend in the 2003 legislature.

During that session,

Nixon ostracized “frivolous” mold claims on his legislative web site and

used a perk only available to lawmaker attorneys to delay the trial of

an insurer that denied a Baptist church’s mold claims. Most importantly,

Nixon authored H.B. 4, a grab bag of lawsuit-limits to benefit every major

industry. This law imposes numerous new hurdles on plaintiffs who seek

to recover damages involving: Medical-malpractice; Nursing homes; Product

liability; Asbestos; Class actions; and Multiple defendants who share responsibility

for an injury.

Apart from the four

local-government clients in the million-dollar club, the industry of every

other million-dollar client urged lawmakers to pass H.B. 4. Four million-dollar

clients testified directly in favor of this legislation: the Texas Medical

Association, the Texas Hospital Association, the Association of Electric

Companies and ExxonMobil.

Plaintiff attorneys

and consumer organization led opposition to this legislation. Trial lawyer

interests spent up to $2.6 million on 2003 lobbyists, led by Asbestos Free

Texas (up to $985,000). The second largest plaintiff client was Linebarger

Heard Goggan ($915,000), a firm that specializes in landing municipal tax-collection

contracts--and fending off related ethics scandals. The Texas Trial Lawyers

Association, the chief opponent of H.B. 4 as a whole, was the next largest

plaintiff client ($650,001). |

TXU’s

Bad Breaks

TXU was one of four

power companies that agreed to pay $10.5 million in 2002 to settle Texas

Public Utility Commission charges that they improperly made $29 million

by manipulating Texas’ deregulated market. TXU became Texas’ largest electric

and gas utility in 1997, when it acquired Lone Star Gas. The merger saddled

TXU with a defective gas pipeline that has caused eight explosions and

five deaths since its installation in the early 1970s. Arguing that replacing

these pipes would cost $130 million, TXU sought Texas Railroad Commission

approval in May 2003 to hit North Texas gas customers with a huge rate

increase. The City of Dallas and other opponents of the rate hike argued

that TXU should eat these costs because it should have foreseen this problem

when it bought the moldering pipeline. Opponents also said repair costs

escalated because the utility failed to tackle the problem sooner. Apart

from its stable of lobbyists, TXU also retained Public Strategies to conduct

a public-relations campaign to counter “fear-mongering” by critics of the

defective pipe. “It was never our intention to prosecute this in the media,”

a TXU spokesperson told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. “But we’ve been backed

into the corner.”

TXU’s rate-hike request

bitterly divided the three Railroad Commissioners, forcing them to choose

between a large bloc of voters and a big campaign donor. The only commissioner

facing voters in 2004, Victor Carrillo held out until the end of a May

2004 hearing before casting the deciding vote to deny most of the rate

increases that TXU sought. Commissioner Michael Williams blasted the decision

as “capricious, contrary to the law and an act of sheer cowardice.” By

voting against the utility, which he said “did not operate in a prudent

manner,” Commissioner Charles Matthews sidestepped a firestorm. Matthews

earlier ignited a 2000 ethics scandal by declining to recuse himself from

a rate-hike request by TXU—the longtime employer of his son.

|

Doctored

Malpractice Claims

A key part of H.B.

4 (see “Damages Control”) capped the damages that Texas courts can award

to medical malpractice victims. The law caps non-economic medical malpractice

damages (for pain, suffering, disfigurement and impairment) at a maximum

of $250,000. Fearing constitutional challenges, lawmakers also floated

a constitutional amendment to allow such caps. The amendment passed in

September 2003—with 51 percent of the vote.

This battle pitted the

medical and insurance lobbies against plaintiff attorneys. As the battle

raged, media stories contained troubling reminders that the state was limiting

malpractice damages--without limiting malpractice itself:

-

Baylor Medical Center doctors

had good and bad news for Nelda Jordan Miles of Grapevine after her February

2003 cancer surgery. The bad news was that they removed the wrong kidney.

The good news was that kidney that they meant to remove was not cancerous,

after all.

-

The Arandas family of East

Texas filed a lawsuit in March 2003 against Baylor Medical Center and Dallas’

Children's Medical Center after an organ-donor blood mismatch killed their

baby girl, Jeanella.

-

Shortly before Texans voted

on the damage-cap amendment, mechanic Hurshell Ralls settled a lawsuit

against the Clinics of North Texas and the two doctors who amputated his

penis after a diagnosis of penile cancer. Post-operative pathology revealed

that Ralls did not have cancer, after all.

Two leading champions

of caps on malpractice damages were the Texas Medical Association and the

Texas Hospital Association, which had maximum lobby expenditures of more

than $1 million apiece in 2003. The pro-caps lobby argued that skyrocketing

malpractice awards triggered skyrocketing malpractice insurance rates that

were putting doctors out of business. If this were true, then capping

malpractice damages would rollback insurance rates and save the medical

profession from extinction. Governor Rick Perry’s Insurance Commissioner,

Jose Montemayor, wrote lawmakers in March 2003 that the proposed caps “would

translate to a 17 percent to 19 percent reduction in rates.” Yet lawmakers

quietly stripped out Rep. Patrick Rose’s amendment to mandate rate reductions.

Lacking such accountability,

just one medical malpractice insurer lowered its rates in early 2004. Montemayor

then told lawmakers in April 2004 that the highly specific numbers that

he cited a year earlier were theoretical figures that were not intended

to suggest that malpractice insurance rates would actually decrease by

any specific amount. In fact, a couple insurers applied to regulators to

increase their malpractice rates by at least as much as Montemayor had

said that rates would fall. When regulators balked at a 19 percent rate-hike

request by GE Medical Protective, this malpractice insurer announced in

2004 that it would dodge regulation altogether. |

Gambling

On Slot Machines

Gambling and Indian

interests carefully laid the groundwork for Governor Rick Perry’s 2004

proposal to raise $2 billion over three years by legalizing video-lottery

slot machines at Texas race tracks and Indian reservations. These two interests

collectively spent up to $4.8 million on 90 lobby contracts in 2003 (Indian

tribes are classified in the Ideological and Single-Issue sector). The

race

track industry hired former Perry Press Secretary Ray Sullivan and paid

more than $200,000 to former Texas Secretary of State Elton Bomer. Gambling

interests also dropped $572,175 into Perry’s war chest in the four years

preceding the governor’s slots proposal (2000-2003).

The top race-track

lobby clients were Magna Entertainment Corp.’s MEC Lone Star, which owns

Lone Star Park in Grand Prairie, and Gulf Greyhound Partners, which owns

Gulf Greyhound Park south of Houston. While lottery contractors such as

GTECH and Oberthur Gaming must compete with slot machines for gambling

dollars, GTECH bet on both ponies by buying a company that makes video

lottery terminals. Finally, the Amusement and Music Operators of Texas

(AMOT) represents owners of “eight-liner” gambling machines. After the

Attorney General’s Office seized more than 2,000 of these illegal machines

in recent years, AMOT urged lawmakers in late 2003 to legalize slot machines

and give its members a piece of the action. But slots and other revenue-raising

proposals crapped out with lawmakers in the 2004 special session.

|

|