January 7, 2009

Reverse Engineering:

Politicians Get Burned Paving Texas Backwards, From the Top Down

“When our hair is gray, we will be able to tell our grandchildren that we were in a TxDOT meeting room when one of the most extraordinary plans was laid out for the people of Texas.”

—Gov. Perry on his Trans-Texas Corridor vision, December 2004

By Laura Bloomer

Two years before the 2006 gubernatorial election, Texas Governor Rick Perry sought to convert the campaign trail into a superhighway by pitching a $175 billion plan to privatize more than 4,000 miles of state roads. Given that this Trans-Texas Corridor (TTC) would be the nation’s largest expanse of privatized highway, nobody could accuse the governor of lacking vision. But Perry’s vision for the mother of all toll roads has inspired more anger than enthusiasm. Socialized highways are one thing that Texans will spend tax money on. Perry’s plan to sow the state with private tollbooths plowed into political roadblocks that have made the governor’s vision seem about as realistic as the children’s fantasy Phantom Tollbooth. On Tuesday, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) officially declared the concept of the project dead – “it is clearly not the choice of Texans.” 1

The TTC plan was to cede large swaths of public highway to the private sector for decades. When a consortium of private companies won a TTC contract, those companies would agree to build and maintain that road for 50 years. The contractor would also agree to pay the state a lump sum up front or pass along a share of the billions of dollars in tolls that it collects over the life of the contract. Despite opposition to the governor’s grandiose vision and the official pronouncment of its death, the state has signed initial development agreements for two stretches of the Trans-Texas Corridor: TTC-35 and TTC-69.

TTC and toll road advocates argue that TxDOT lacks sufficient funds to supply the state’s burgeoning population with adequate infrastructure.2 This shortfall, they argue, all but forces the state to turn to private investors, who offer innovative funding packages and can build and maintain roads more efficiently.3 Although used to promote numerous privatization initiatives in Texas, this efficiency theory frequently has failed to materialize in practice. The state of Texas has awarded billions of dollars in privatization contracts for prisons, Medicaid HMOs, human-service eligibility, food-stamp-fraud prevention and state payroll payments. Yet it would be dishonest to suggest these costly privatization boondoggles have paid efficiency dividends to taxpayers.4 In the latest privatization scandal, the Texas Attorney General outsourced its case-management system to IBM, which realized some short-lived cost savings by failing to back up this crashing computer system.5

Despite this dismal track record, the Austin lobby is full of enthusiastic promoters of all manner of privatizations—including toll roads. Highway contractors and other would-be tollbooth operators warmly received Perry’s TTC vision.

Since the state solicited its first bids for a leg of the TTC project in 2003, private companies that have landed lucrative TTC contracts have contributed $3.4 million to Texas candidates and political committees—a significant increase in their political activity. TTC contractors also have spent up to $6.1 million on Texas lobbyists since the state solicited their respective bids. While the TTC contains windfalls for some contractors, lobbyists and elected officials, the benefits to Texas motorists and taxpayers are much less clear. |

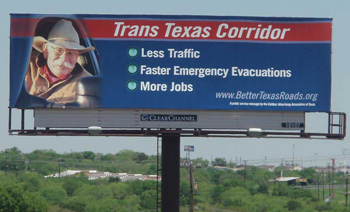

Billboard advertising the TTC to Texas motorists and taxpayers.

|

Texas-Sized Toll Roads

Budget-crunched statehouses across the country increasingly are turning toward privatized pavement. Half of the states already have passed legislation permitting highway sales or leases, with one-third of these states passing the measures within the last three years.6 Texas is one of three pioneer governments that have begun to set their highway privatization policies in concrete. A consortium headed by Australia’s Macquarie Infrastructure Group and Spain’s Cintra Concesiones de Infraestructuras de Transporte agreed to pay the City of Chicago $1.8 billion in 2005 to lease the eight-mile Chicago Skyway for 99 years. The same consortium signed a bigger $3.8 billion deal the following year to operate the Indiana Toll Road for 75 years.7

While the TTC is similarly structured, the 157-mile Indiana Toll Road is puny by comparison. It would take more than 25 of those Hoosier highways to cover Governor Perry’s 4,000-mile TTC route. The TTC plan boasts four “priority” corridors, each a quarter-mile wide. If fully built, the corridors would feature six car lanes, four truck lanes, six rail lines and contain honeycombs of cables and pipelines for communications, electricity, water, oil and gas. Building out Perry’s TTC vision would require the state to leverage eminent domain to acquire almost 600,000 acres of private land, the equivalent of condemning 90 percent of Rhode Island. TTC cost estimates exceed $200 billion.8 Yet in one respect, Indiana retains bragging rights over Texas. The Indiana Toll Road has been up and running since the 1950s (it switched to private management just recently), whereas most of the Trans-Texas Corridor remains a Perry pipe dream.

When then-Lieutenant Governor Rick Perry replaced resigning Governor George W. Bush in late 2000, he came to office with established relationships with highway contractors. From mid-1997 to mid-2001, TxDOT contractors contributed $239,750 to Perry. During Perry’s first nine months in the Governor’s Mansion his administration awarded almost $1 billion in contracts to these same TxDOT contributors.9 Nonetheless, TxDOT was issuing warnings that dwindling road funds would postpone crucial highway projects. The 2001 legislature proposed a constitutional amendment to revamp the state’s pay-as-you-go road funding. Governor Perry promoted passage of the amendment in ads selling fast, tax-free roads. Those ads made no mention of eminent domain or tollbooths. In a special constitutional-amendment election in November 2001, 68 percent of voters approved Proposition 15. It created the bond-issuing Texas Mobility Fund and granted TxDOT broad discretion to finance transportation projects as it sees fit.

Two Legs

Perry signs the first TTC bill into law in 2003. Photo by Texas A&M University |

The TTC moved into the fast lane in June 2003, when Governor Perry signed legislation into law that authorized the TTC and expanded TxDOT’s road-privatization powers.10 That same month TxDOT solicited its first proposals for a segment of the TTC. TTC-35 is slated to run parallel to I-35, ultimately connecting the Oklahoma and Mexico borders between Gainesville and Laredo.11 So far, TxDOT has sought proposals for a 316-mile chunk of TTC-35 from Oklahoma to San Antonio. In March 2005 the five gubernatorial appointees to the Texas Transportation Commission awarded a preliminary development agreement for the northern segment of TTC-35 to a consortium led by Spain-based Cintra and San Antonio-based Zachry Construction Corp.12 |

Since construction is contingent upon pending state and federal environmental studies, this team is only authorized to design the roadway. Cintra-Zachry later gets to make the first pitch for the mega-contract to build, maintain and operate this toll road (though TxDOT can seek competitive bids if it chooses).13 In a revised development plan, TxDOT announced in 2006 that the winner of the final contract for this stretch of highway will pay the state $2.3 billion and invest an estimated $8.8 billion to build, maintain and operate it over the course of 50 years.14

In June 2008, the Transportation Commissioners awarded a similar preliminary development agreement to another consortium led by Zachary and Spain-based ACS Infrastructure.15 This contract covers TTC-69, which would run from the northeast corner of the state through Houston to McAllen and Laredo.16

Paving the Campaign Trail

Six years after Governor Perry unveiled his TTC vision, the state has signed initial development agreements for two legs of the project.17 Both of the consortia that won contracts to design a leg of the TTC boast a team of finance companies, construction companies and law firms.18 Since their respective TTC proposals were first requested, the PACs and executives of these consortia members have flexed their private-sector assets, contributing a total of $3.5 million to state candidates and political committees.

Texas Political Contributions By TTC Contractors

|

Some TTC contractors have diverse interests beyond the TTC. Law firms involved in TTC consortia, for example, make political contributions to advance their lobby practices and pour money into state judicial races. Nonetheless, interesting trends emerge when just the political contributions of TTC contractors from the construction industry are analyzed independently.

TTC-35 Construction-Industry Contributions, 1999-2006

(Zachry Construction, Pate Engineers & Othon)

TTC-69 Construction-Industry Contributions, 1999-2006

(Williams Bros., Ballenger Construction, Parsons Corp. & Klotz Assoc.)

During the 2000 election cycle, before Governor Perry unveiled his TTC vision, three construction-industry members of the future TTC-35 consortium (Zachry Construction, Pate Engineers and Othon) made relatively modest political contributions of $113,280. In the following 2002 election cycle, when Governor Perry unveiled his TTC vision (see accompanying graph), these three companies more than tripled their state political activities.

Construction-industry members of the TTC-69 consortium (Williams Brothers, Ballenger Construction, Parsons Corp. and Klotz Associates) similarly tripled their political contributions in the 2002 election cycle. Their political activity then subsided in the 2004 cycle, only to soar when TxDOT solicited TTC-69 proposals in 2006.

The favorite candidate of TTC contractors was Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst, followed by Governor Perry. The governor collected 63 percent of his TTC-related money from just two highway tycoons: Zachry Construction’s H.B. Zachry ($125,000 to Perry) and James Pitcock of Williams Brothers Construction ($100,000).

Top Recipients of TTC-Contractor Contributions

*Sits on Senate Transportation Committee, chaired by Sen. Carona. Note: Contributions for TTC-35 contractors cover July 2003 – July 2008. Contributions for TTC-69 contractors cover January 2006 – July 2008. |

Since their respective TTC proposals were first requested, TTC contractors also spent from $2.7 million to $6.1 million on 163 Texas lobby contracts. (Texas lobbyists report contract values in ranges rather than exact amounts). After a populist backlash against privatized toll roads erupted during the 2007 legislative session, Cintra almost tripled its lobby spending. The Spanish company ramped up its maximum Texas lobby expenditures from $105,000 in 2007 to $280,000 in 2008.

Texas Lobby Contracts By Trans-Texas Corridor Contractors

Note: Lobby contracts tracked since proposals were requested for TTC-35 or TTC-69.

|

TTC contractors hired some of Texas’ leading revolving-door lobbyists. One is former lawmaker Dan Shelley, who served as legislative director to Governors George W. Bush and Rick Perry. Perry hired Shelley in September 2004, just months before Cintra won the $6 billion contract to develop TTC-35. The Dallas Morning News subsequently reported that Cintra had hired Shelley as a consultant before he went on the governor’s payroll, but Shelley had not registered as a Cintra lobbyist.20 When Shelley left Governor Perry’s office a year later, he went back to work for Cintra—this time as a registered lobbyist.

Top TTC Lobbyists

Note: TTC-35 contracts cover 2003 - 2008; TTC-69 contracts cover 2006 - 2008.

|

Another alumnus of Governor Perry’s office is former press secretary Ray Sullivan, whom Swiss bank UBS hired as its top contract lobbyist during the period that TTC-69 has been in play. UBS boasts an even bigger tie to Texas’ toll-road visionary. Not running for reelection in 2002, retiring U.S. Senator Phil Gramm contributed $610,000 of his war chest to Governor Perry in the largest same-day contribution of Perry’s career.21 After Gramm left the Senate, UBS hired him as a vice chair and lobbyist. Gramm then pitched the Perry administration on plans to take out life insurance policies on state employees and privatize the Texas Lottery. These schemes have not gotten off the ground.22 Gramm registered as a federal UBS lobbyist from 2004 through 2007 but never registered to lobby in Texas.23

Trans-Texas Corridor Blowout

Governor Perry, highway contractors, lawmakers and the lobby had a good run down the Trans-Texas Corridor before the public crashed their tailgate party. State officials have argued that Texas voters endorsed the TTC when they approved Proposition 15. Yet Governor Perry did not unveil his $175 billion tollbooth vision until January 2002—two months after Proposition 15’s passage. Arguing that their plans contained proprietary information, TxDOT and Cintra even went so far as to file a lawsuit against Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott in a failed effort to keep their TTC-35 contract secret.24

As details of Governor Perry’s tollbooth vision trickled out over the information superhighway, public road rage ensued. The strongest opposition came from rural landowners who chafed at the staggering amounts of private land that the mammoth project would condemn. Recoiling from a U.S. Supreme Court decision that expanded eminent domain powers, the Texas Legislature passed special legislation and appointed an interim committee on eminent-domain abuse in 2005.25 Upon being appointed co-chair of that panel, Rep. Beverly Woolley (R-Houston) warned that “it is important that private property be protected” and “eminent domain should be used in limited circumstances for necessary, traditional, public uses.” 26 Yet earlier that year, Texas Transportation Commissioners—exercising authority recently handed to them with legislative approval—awarded the first contract for the TTC, a highway plan that was seeking to condemn mind-numbing amounts of private land for privately operated toll roads. Yet earlier that year, Texas Transportation Commissioners—exercising authority recently handed to them with legislative approval—awarded the first contract for the TTC, a highway plan that was seeking to condemn mind-numbing amounts of private land for privately operated toll roads.

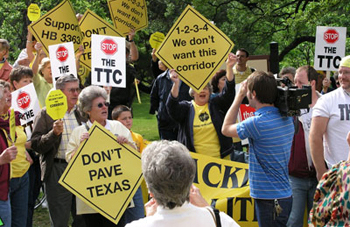

On the floor of the legislature, Texas lawmakers can listen to themselves for hours extolling the virtues of privatization and tax-free roads. But it’s much tougher back in the district. There it fell to tongue-tied legislators to explain to ranchers how it is in their best interest for the state to condemn their ranchland and sign it over to a Spanish company that will charge them tolls to drive their trucks over what once had been their family’s land. |

Protest against the TTC held in Austin, TX. By Corridorwatch.org. |

A State Auditor report released in February 2007 found that TxDOT’s opaque accounting made TTC costs difficult to estimate. Nonetheless, the auditor estimated that TTC-35, which was billed as a clever way to privately finance public roads, could cost taxpayers $30 billion.27 TxDOT accounting was based on a vanishing asset: Trust. A week later legislators convened a crowded hearing in which lawmakers and citizens took turns expressing their mutual distrust of the agency. Lawmakers who had pressed the TTC accelerator in the 2003 and 2005 sessions now expressed their outrage that the toll-road scheme was careening out of control. This all occurred a full year before TxDOT revealed that it had made a $1.1 billion accounting error by counting the same revenue twice.28

In 2007 an almost unanimous majority of the Texas Legislature passed a TTC moratorium bill.29 Governor Perry vetoed the bill and threatened to call a special legislative session if lawmakers crashed through his veto barricade. Instead, lawmakers passed a weaker bill that limited future road privatizations to 50 years, gave regional mobility authorities more power to bid on road projects and put a two-year moratorium on road privatization deals. 30 Yet most private toll projects then in the works drove right through the moratorium’s prodigious loopholes. One year into the so-called moratorium, for example, the Transportation Commissioners awarded the TTC-69 contract to the Zachry/ACS consortium.

In early 2008 TxDOT took the extraordinary step of convening meetings along the projected route of TTC-69 to gather public input about the project. Approximately 12,000 Texans showed up, overwhelmingly denouncing the project. After the meetings, TxDOT officials said that they would recommend a new route for the road that would prevent the state from having to condemn huge swaths of privately owned rural land. Instead, the agency allowed that it could run the road along existing highways SH-59 and SH-77.31 Governor Perry, the legislature and TxDOT spent six years building a newfangled, complex machine that was supposed to spew out a monster highway system in record time while delivering staggering efficiencies and cost savings to the people. Yet how much time and money might have been spared if the politicians, lobbyists and contractors had started this process six years earlier by asking the people of Texas what kind of highway system they wanted?

Some will rob you with a fountain pen. - Woody Guthrie

“Watch Your Assets” is a Texans for Public Justice project.

Lauren Reinlie, Project Director.

Author Laura Bloomer was an intern at Texans for Public Justice.

Endnotes:

1 “Trans Texas Corridor is dead, TxDOT says,” Michael A. Lindenberger. Dallas Morning News. January 6, 2009.

2 One factor in these budget constraints is the state’s low 20-cent-per-gallon gasoline tax, which the legislature has not increased since 1991. See “Senator Carona: Gas Tax Goes Up or Prepare to Pay the Toll,” David Schechter, WFAA-TV. September 22, 2008. Funding roads through gas taxes has some equity appeal, given that the more you drive, the more you pay. Such funding also rewards fuel efficiency, which is sensible in a state where the biggest cities flunk federal air standards.

3 The state argues that package-deal contracts that combine highway design, construction and maintenance will create efficiencies that were absent under the state’s traditional approach of awarding separate contracts for each piece of the puzzle. Yet this approach sacrifices the checks and balances that exist when competing designers and builders hold each other accountable for mistakes or padded budgets. “State shifts road work to high gear,” Tony Hartzel, Dallas Morning News. October 13, 2003.

4 See previous Watch Your Assets reports: “Peddling Privatization Boondoggles,” July 18, 2007; and “Lax Oversight Plagues Private Prisons,” February 6, 2008 (http://www.tpj.org/watchyourassets/hhsc and http://www.tpj.org/watchyourassets/prisons).

5 “Computer crash hinders Texas Attorney General's Medicaid fraud case,” Emily Ramshaw and Robert Garrett, Dallas Morning News. October 23, 2008.

6 “Leasing of Landmark Turnpike Puts State at Policy Crossroads,” Craig Karmin, Wall Street Journal. August 26, 2008.

7 “Investing in the Fast Lane,” Joanna Slater, The Wall Street Journal. June 13, 2007

8 “Proposal in Texas for a Public-Private Toll Road System Raises an Outcry,” Blumenthal, Ralph. New York Times. Feb. 10, 2008. “Public meetings air worries about giant Texas highway project,” Graczyk, Michael. Associated Press. Jan. 17, 2008.

9 “The Highwaymen: Perry’s Political Tollbooths Line $1 Billion of State Roads,” Lobby Watch, Texans for Public Justice. October 24, 2001.http://www.tpj.org/page_view.jsp?pageid=859&pubid=623

10HB 3588. http://www.legis.state.tx.us/BillLookup/History.aspx?LegSess=78R&Bill=HB3588

11 “TTC-35 Tier One Draft Environmental Impact Statement: Tier One Preferred Corridor Alternative Map,” Texas Department of Transportation. April 4, 2006. http://www.keeptexasmoving.com/var/files/File/TTCPrjctsTTC35/EnvStdyMaps/Tier1DEIS_FEIS/Tier_1_DEIS

/document/chapter_7_figure_7-1.pdf

12 TxDOT paid a stipend to the two losing bidders, led by Flour and Skanska.

13 This excludes the SH-130 stretch of highway around Austin, which already was under construction. Comprehensive Development Agreement Overview. March 11, 2005. http://ttc.keeptexasmoving.com/pdfs/projects/ttc35/final cda overview.pdf

The contract also grants Cintra/Zachry the first shot at any future contract to extend TTC-34 from San Antonio to the Mexico border.

14 “Corridor toll road may cost $8.8B,” Hartzel, Tony. Dallas Morning News. Sept. 29, 2006. And, “Master Development Plan: TTC-35 High Priority Trans-Texas Corridor: Executive Summary,” Texas Department of Transportation. September 2006. http://www.keeptexasmoving.com/index.php/ttc_35_mdp

15 “Cintra/Zachry Team Fact Sheet,” Texas Department of Transportation. http://www.corridorwatch.org/ttc/pdf/fact sheet - Cintra-Zachry - 031105 FINAL.pdf

And, “I-69 Public Private Partnership Comprehensive Development Agreement: Recommendation for Conditional Award,” Presentation to Texas Transportation Commission, produced by the Texas Department of Transportation. June 26, 2008. http://keeptexasmoving.com/var/files/File/I69TTC_CDA/I69TTCCommissionPresentation.pdf

16 “I-69/TTC Tier One Draft Environmental Impact Statement: Upgradeable Corridor Map,” Texas Department of Transportation. June 2008. http://www.keeptexasmoving.com/var/files/File/TTCPrjctsI69TTC/EnvStdyMaps/Tier1DEIS_FEIS/

I69TTC_Map_and_Fact_Sheet.pdf

17 These agreements are called Comprehensive Development Agreements (CDAs) and they act as planning proposals for public-private partnerships.

18 “Cintra/Zachry Team Fact Sheet,” Texas Department of Transportation. http://www.corridorwatch.org/ttc/pdf/fact sheet - Cintra-Zachry - 031105 FINAL.pdf

And, “I-69 Public Private Partnership Comprehensive Development Agreement: Recommendation for Conditional Award,” Presentation to Texas Transportation Commission, produced by the Texas Department of Transportation. June 26, 2008. http://keeptexasmoving.com/var/files/File/I69TTC_CDA/I69TTCCommissionPresentation.pdf

19 Price Waterhouse Coopers, which is a member of the Cintra-led TTC35 consortium, previously advised the Regional Transportation Council that it should accept Cinta’s bid for the SH 121 contract over that of the public North Texas Tollway Authority. Evenually, NTTA won the rights to operate SH 121. “Cintra gets a boost,” Michael A. Lindenberger and Jake Batsell, Dallas Morning News. June 15, 2007.

20 “Trans-Texas firm hired ex-Perry aide: He worked before for company that won bid for transit corridor,” Pete Slover and Tony Hartzel, Dallas Morning News. August 18, 2006.

21 On October 15, 2002, Friends of Phil Gramm contributed $300,000 to Governor’s Perry’s campaign directly. The Perry campaign also reported that Gramm’s committee spent another $310,000 that same day on a media buy benefiting Governor Perry. This money was not counted as a TTC-contractor contribution because Gramm was not then working at UBS and Texas had yet to request TTC proposals.

22 TPJ’s “Privatizing the Lottery Raises Gambling Stakes,” March 26, 2008. http://www.tpj.org/watchyourassets/lotterysale See also “John McCain’s Gramm Gamble,” Texas Observer, May 30, 2008. http://www.texasobserver.org/article.php?aid=2767

23 Texas lobbyists generally must register if they get paid more than $1,000 a quarter and spend more than 5 percent of their compensated time on lobby activities.

24 “State to seek corridor plans from 2 firms,” Sallee, Rad. Houston Chronicle. Sept. 29, 2006.

25 In 2005 the Texas Legislature passed SB 7 to reverse the effects of the U.S. Supreme Court’s controversial Kelo v. City of New London,decided June 23, 2005.

26 “Speaker Craddick appoints Rep. Beverly Woolley as co-chair to the Interim Committee to Study the use of the Power of Eminent Domain,” Texas House news release, October 14, 2005.

27 “Audit rebukes costs; Report says TxDOT estimates unreliable for Trans-Texas plan,” Robison, Clay. Houston Chronicle. Feb. 24, 2007.

28 “State road officials say they erred by $1 billion,” Wear, Ben. Austin American-Statesman, February 6, 2008. “Audit explains TxDOT error,” Wear, Ben. Austin American-Statesman, August, 29, 2008.

29 HB 1892. http://www.legis.state.tx.us/BillLookup/History.aspx?LegSess=80R&Bill=HB1892

30 SB 792. http://www.legis.state.tx.us/BillLookup/History.aspx?LegSess=80R&Bill=SB792

31 “TxDOT moves to reroute I-69 dispute; State now says the Trans-Texas Corridor will stick to major highways,” Sallee, Rad. Houston Chronicle. June 11, 2008.